Chinese Lotteries in Emeryville

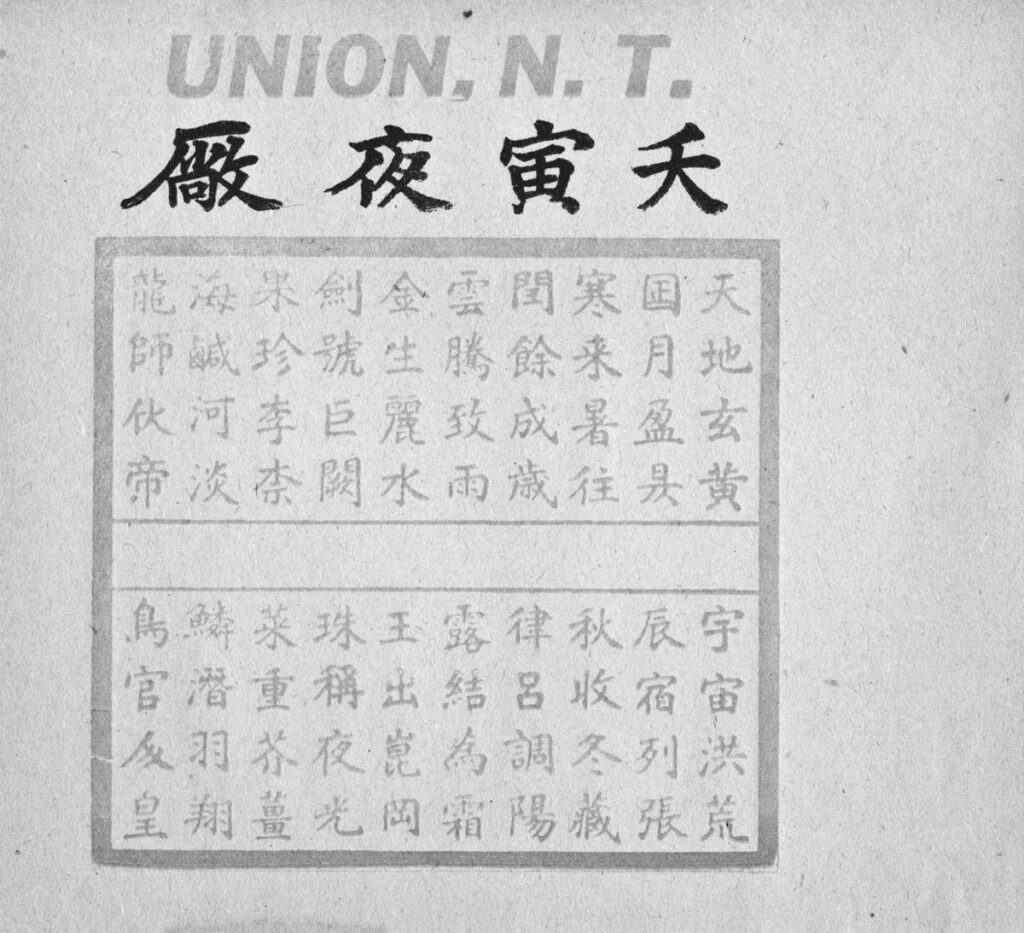

The lottery played in Emeryville from the twenties through the forties originated in China during the Han dynasty. According to Stewart Culin in his Gambling Games of the Chinese in America (Gambler’s Book Club, 1972), the lottery was traditionally known as “Pak kop piu” (white pigeon ticket) because pigeons were used to carry the tickets and winning numbers. Its purpose was to raise money for the army. The game came to California in the 1840s, Culin wrote. The tickets displayed the first eighty characters of the Chinese Thousand Character Classic “so well known in China that its characters are frequently used instead of the corresponding numerals from one to one thousand,” he noted.

Lotteries Everywhere

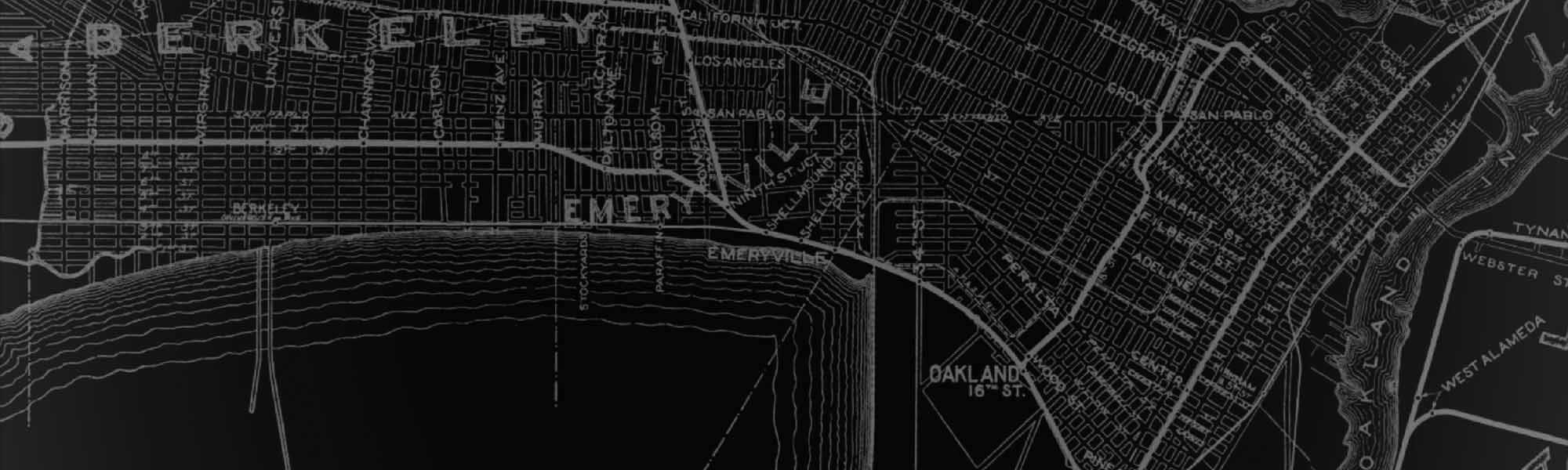

According to Henry Lyman, retired fire chief and longtime Emeryville resident, the lotteries were located “all up and down Park Avenue and at 65th and Hollis.” They could be found in garages, in the backs of restaurants, and in shanties built especially to house them. Chinese restaurants such as the Alamo Club at the foot of Park Avenue were state chartered, and only Chinese could go there. The Alamo also offered Fan Tan and Pai Gow. The San Pablo Hotel had a Chinese restaurant where the lottery was played; other locations included the Harlan Street Cafe, the Watts Street Cafe, the building at 1145 Park Avenue (now Fantasy Junction), and the Mascot Rooms. The Sanborn Insurance maps of this period show fourteen establishments called Variously “Chinese,” “Chinese Club” and “Chinese Gaming” along Park Avenue.

Only Cost a Dime

The lottery was very popular with working people, many of whom were employed at the Judson Steel Mill at the end of Park Avenue. Because it only cost a dime, poor people could afford it as well. The game was played openly in Emeryville, even by the police. According to Lyman, the lottery worked as follows: “There were runners; they stand out there—you put your dime out and mark your ten spots. It’s a keno game… they weren’t legal, but nobody bothered them.” This was said of the lottery in the forties, when there were half a dozen companies, such as Fook Tai and Union, each with its own tickets and drawings.

According to Emeryville old-timer Slim Collier, there were even more companies in the twenties. Ten had drawings at night (N.T.) and one in the afternoon. When the runners came around, you handed in your ticket marked with a Chinese brush or anything at hand; ink brushes were available in the stores. Everyone knew when the runners would come. They also brought the tickets back to the same lottery joint where the players submitted them, along with any winnings.

Prohibition Era

During Prohibition, the city of Emeryville tolerated—or maybe encouraged—liquor and gambling, but Alameda County didn’t. County agents, led by Earl Warren, then the District Attorney, raided the lotteries as well as the speakeasies and bootleggers. Some speculated that these raids were on businesses that didn’t pay protection, since not all were raided. The Lincoln Cafe on Adeline Street was raided a number of times and had to rent a garage to keep its customers. Lottery players felt safe when caught in a raid. because the Chinese always posted bail. Collier tells of a time in the early twenties when there was a loud crash at Mrs. Milani’s house. located between two Chinese clubs. It was the Chinese, using an established escape route during a raid. They ran in Mrs. Milani’s back door and out the front.

End of the Lottery

The Emeryville lotteries died out in the fifties; it isn’t clear why. Although there were no raids at this time. it is possible that organized gambling interests in Reno—who had to pay big license fees—resented Emeryville’s lottery. Moreover, it had poor odds. Riddle’s Weekend Gambler’s Handbook refers to keno as “a good game to stay away from” adding, “If you plan to play keno, give the money to charity instead, because you can count on being parted from it, and a gift to charity might give you some satisfaction, whereas losing money at keno won’t.”

This story originally published in 1996 for the Emeryville Centennial Celebration and compiled into the ‘Early Emeryville Remembered’ historical essays book.