African Americans in Early Emeryville: 1870-1950

By Donald Hausler

Emeryville evolved as an ethnically diverse community, and African Americans, Chinese, and Japanese contributed to its early development.

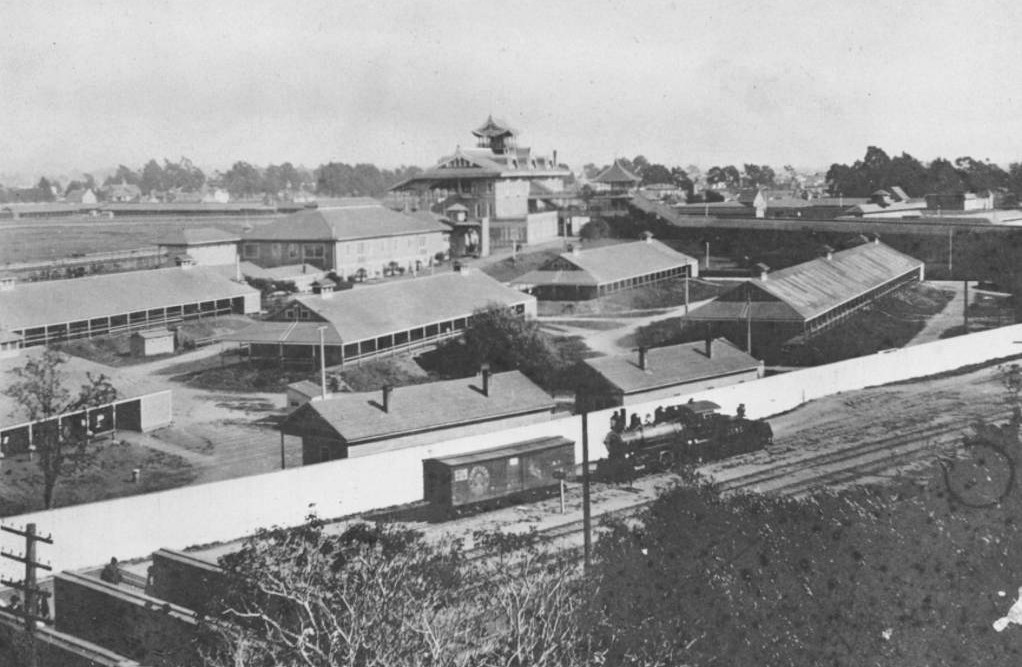

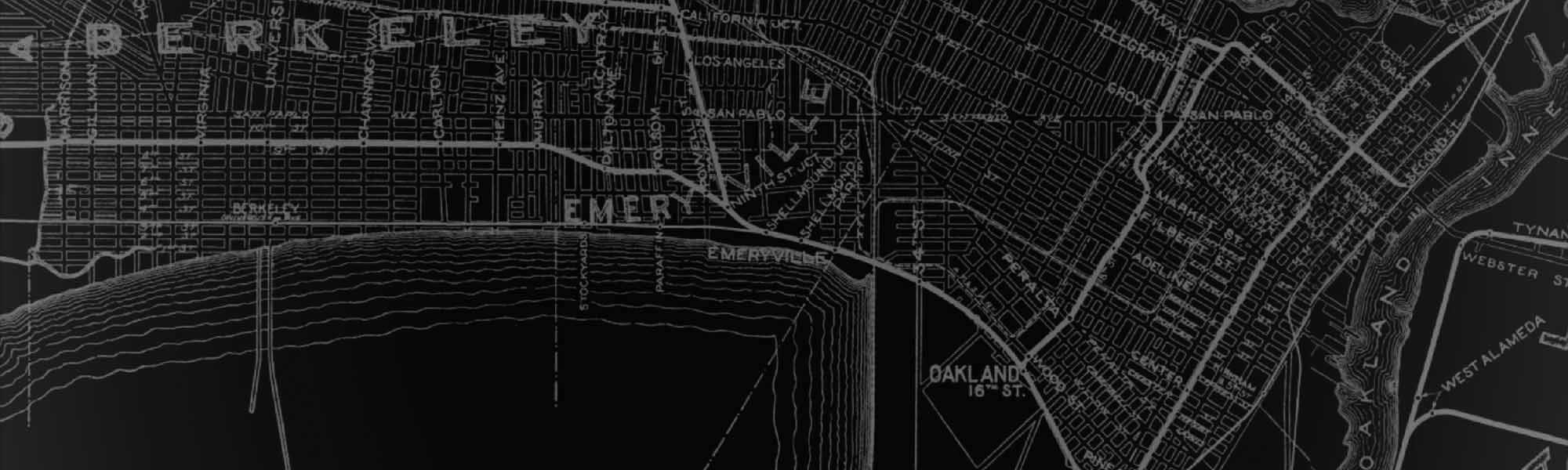

Oakland’s tiny northern suburb emerged in the 1880s as a railroad, industrial, and commercial center, and also became a tourist attraction in the late nineteenth century. Two large parks opened in Emervyille in the 1870s. Oakland Trotting Park, built in 1871, featured a one mile race track that stabled over 300 horses. Shell Mound Park, built five years later, functioned as a picnic resort and amusement park. From 1890 to 1910, Emeryville’s African American work force found employment at the Oakland Trotting Park, as well as in the factories and on the railroad. Several African Americans were working at Emeryville factories of the 1890s, according to the 1900 census. John Bost, his wife Lucy, and their four children lived on Park Avenue in Emeryville. Bost worked as an iron heater at the Judson Iron Works, at the time the largest industry in Alameda County. Several African American boarders lived at his residence, many of whom also worked at Judson.

Trotting Park spanned from Park Avenue all the way to what is now Stanford Avenue (Map OaklandWiki).

African Americans were also employed at Butchertown, the stockyard district of Emeryville. The 1910 census identifies Henry Rogers, an African American from Kentucky, as a laborer in the hide cellar. Two of his sons worked in a Butchertown sausage factory.

A significant number of African American women worked at Virden Canning Co. on Park Avenue in the 1920s. Built in 1918 by Chinese capitalists, the firm operated as a meat and fish packing plant; in 1927, California Packing Corp. purchased the plant and converted it to a peach cannery. Both firms also employed a large number of Italian and Portuguese women during the canning season. Employees lived in company-owned cabins located east of the plant.

Black Occupations

African Americans also worked in non-factory occupations in early Emeryville. The 1900 and 1910 censuses list African Americans working as white-washers, laborers, shipping clerks, and as railroad porters and dining car waiters. The latter two occupations were for the Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe, the two major railroads that served the town.

African Americans also operated businesses in early twentieth century Emeryville. The 1910 census lists William Walden as the African American proprietor of a restaurant. According to the records of the Northern California Center of Afro-American History and Life, F. Kaleel, an African American, owned an ice cream business at 4065 San Pablo Avenue in the 1920s.

The horse race track became the largest employer of African Americans in early Emeryville. For the first 25 years of its existence, the Oakland Trotting Park featured harness racing, a sport in which a driver rides in a sulky light two-wheeled vehicle pulled by a trotting horse. William Johnson, an African American trainer and driver, had the largest stable of trotting horses at Oakland Trotting Park in the mid-1890s, according to an 1895 San Francisco Chronicle article:

William Johnson, known on every race track in the country…has the largest string at the track. He has twenty-three crabs (trotting horses) in his lot and it is a funny sight to see the old colored driver sending one down the stretch. He drives an old-fashioned sulky with wheels reaching as high as his head. His whip is an old affair with the end turned up the reverse way. On his horse are boots and trotting trappings from the ears down. With a cigar in his mouth the peak of his cap blown up until it stands perpendicular and his coat tails flying out behind the sulky. this fellow, who is as black as ink. comes tearing down the stretch. with every wag at the track jeering. He takes the “Joshing” good-naturedly; in fact. he loves it.

Johnson’s career as a trainer and driver spanned several decades.

The training, feeding, and grooming of the 300 thoroughbred horses stabled at the Emeryville race track required a large work force. From 1900 until the track closed in 1911, the California Jockey Club hired a large number of African Americans to train and care for the horses. The 1910 census identifies approximately 40 African Americans who worked at the race track in the following capacities: stablemen (6), grooms (20), horse trainers (3), cooks (5), and jockeys (4). Many African American employees were from Kentucky, a state with a long tradition of horse training, racing, and breeding. Race track workers lived in dormitories located on the race track grounds.

The Oakland Trotting Park, built by Edward Wiard in 1871, was originally in unincorporated Alameda County, located north of Emery Tract and west of San Pablo Avenue (Photo OaklandWiki).

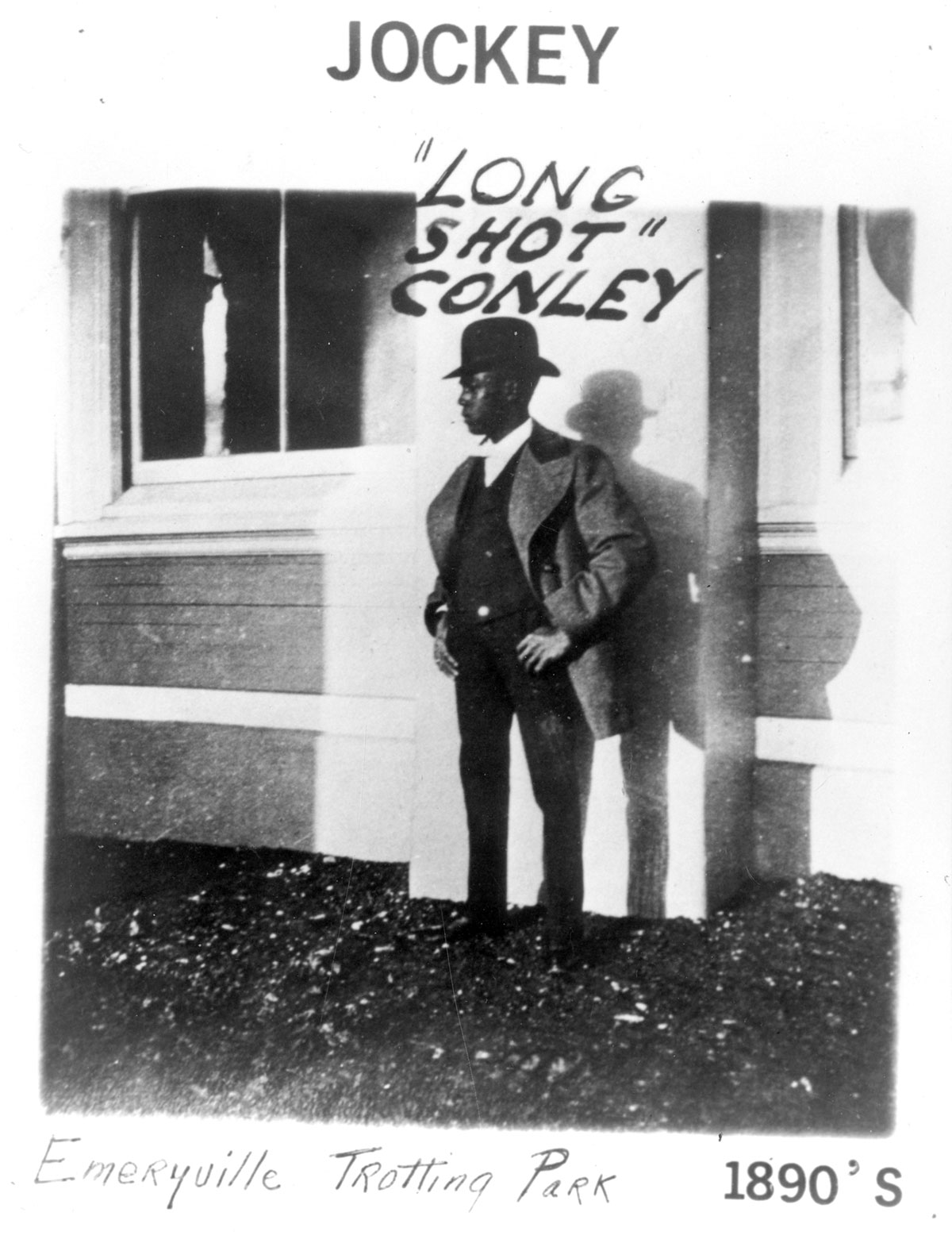

Jess Conley

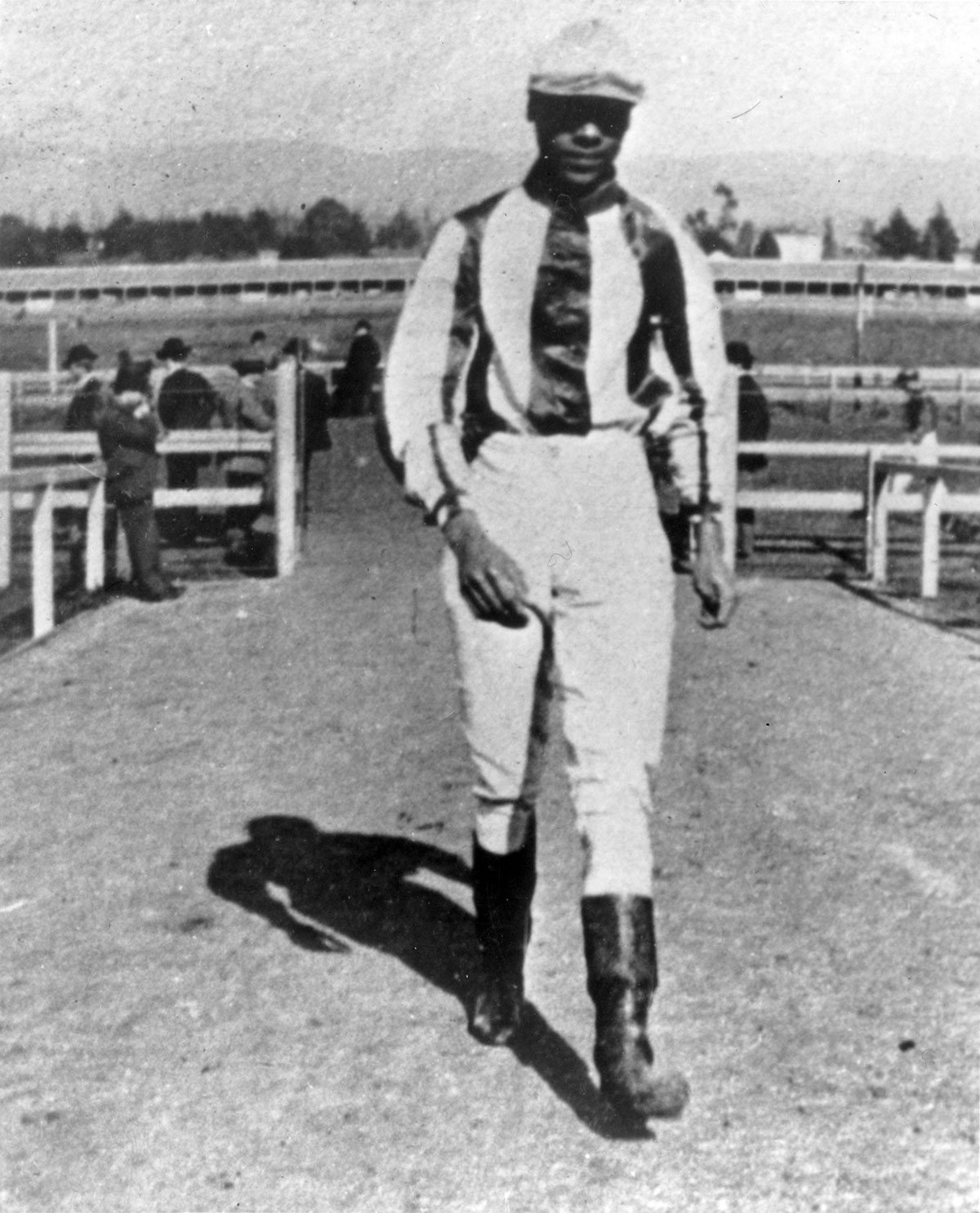

From 1890 to 1911, a significant number of African American jockeys raced at the Emeryville track on a regular basis, including Jess “Longshot” Conley, Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton, Felix Carr, Willie Simms, Andrew Thomas, Monroe Johnson, James Coles, Frank Bowers, and John H. Smith. The 1890s is now considered the golden age of Emeryville’s African American jockeys. Conley, Clayton, Carr, and Simms had outstanding careers in this decade, and their names remain prominent in the annals of horse racing history.

Conley won many races at the Emeryville track in the 1890s, with 1898 his best year. That year Tod Sloan, a famous white jockey who had already conquered the race tracks of America and England, made an appearance at the California Jockey Club. Conley, described by one newspaper as the “ebony hued demon,” defeated Sloan in two races. In the first race Sloan rode the favorite Wawona, while Conley, living up to his nickname, rode 30 to 1 shot Our Climate to victory.ll In the second race, this time aboard Libertine, Conley once again placed first. The same year he won the Latonia Derby in Kentucky.

Conley’s career as a jockey continued into the 20th century. In 1911 he took third place in the Kentucky Derby. He was the last African American jockey to ride in this classic race.

Alonzo Clayton

Alonzo Clayton, another famous African American jockey who raced at Emeryville in the 1890s, began his spectacular career at an early age. He won the Kentucky Derby in 1892 when he as only 15 years old. Over the next six years Clayton won races all over the United States, including the Alabama Stakes (1892), Kentucky Oaks (1894), Great Western Handicap (1897), and the Clark Handicap (1897).

In 1898 “Lonnie” Clayton won his greatest California race. On April 2, Clayton rode Traverser and led the race from start to finish. According to a contemporary account, Clayton rode “with rare judgment and had gotten every ounce out of his mount.”

Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton a famous black jockey, won the Kentucky Derby in 1892 when he was only 15 ears old (Photo: African American Museum Library at Oakland).

Felix Carr, another African American jockey who raced at the California Jockey Club, had acquired a reputation as a winner by the early 1890s. In 1895 Carr won the Burns Handicap, an important California race, and he soon became “the idol of the California turf.” By 1896, however, Carr had “grown too heavy to ride in ordinary events, and devoted his time to learning the art of training.”

Willie Simms was probably the greatest African American jockey to race at the Emeryville track. Born in 1870, Simms won a succession of famous races all over the United States and England, including the Kentucky Derby (twice, in 1896 and 1898) and the English Sweepstakes. Simms became a popular jockey at the Emeryville track in the 1890s. According to one account, “he was a premier in the saddle, honest and fearless …” He died February 26, 1927.

African American jockeys also raced at the California Jockey Club after the tum of the century. The 1910 census identifies four: Monroe Johnson, James Coles, Frank Bowers, and John H. Smith.

Emeryville’s race track era came to an abrupt end when the State Legislature passed an anti-betting bill in 1910 that forced the California Jockey Club and all other California race tracks to close. The last race at Emeryville was run on February 15, 1911. On December 15, 1915, a fire swept through the race track complex, destroying all of the buildings. The closing of the California Jockey Club, which in 1910 was the largest employer of African Americans in the city, was a disaster for Emeryville’s African American work force.

The end of the African American jockey phenomenon in California coincided with a decline of opportunities for African American jockeys all over the United States. In 1894 an association known as the Jockey Club was formed to license riders. Controlled by white interests, it managed to exclude African American jockeys from competition. By the second decade of this century African American jockeys had been eliminated from the sport of horse racing. Their exploits, however, should not be forgotten. From 1880 to 1905, a 25-year period, African American jockeys won thirteen Kentucky Derbies-a statistic that reflects the African American domination of horse racing in the 19th century.

Wilson emerging from the Oaks dugout to shake hands with Earl Rapp at a game in 1949 (Photo: Rodoni Family Collection).

Artie Wilson

African American athletes also excelled at baseball in Emeryville. Oakland Baseball Park, built in Emeryville in 1913, became the home of the Oakland Oaks, a Pacific Coast League team formed in 1903.

Artie Wilson was the first African American baseball player to play for the Oaks. Born in Alabama in 1920, Wilson played for the Birmingham Black Barons for five seasons before he was signed by the Oaks in 1949. A hard-hitting infielder, Wilson led the league during his rookie year in batting (.348) and in stolen bases. Wilson played for the Oaks for only one season; he missed the glorious 1950 season when the Oaks won the Pacific Coast League Championship. In 1951, Wilson played for New York in the Major Leagues, but his baseball career seems to have ended that year.

Photographs of Willie Simms. Jess “Longshot” Conley, Felix Carr, Alonzo (“Lonnie”) Clayton, and Arthur (“Artie”) Wilson are in the archives of the Northern California Center for Afro-American History and Life, located at 5606 San Pablo Avenue in Oakland, only a few blocks from where these athletes originally performed.

Feature Image: Artie Wilson (Doug McWilliams Collection).

Frako Loden

Wow! What a treasure trove of East Bay history. Thanks for this informative article!

yvonne giles

This is a great article! Your information about the race track is much appreciated. Today, after finding your sight, I let my friends know.

So very glad you are preserving AND presenting the areas’ history. Thank you