The History of Emeryville Town Hall

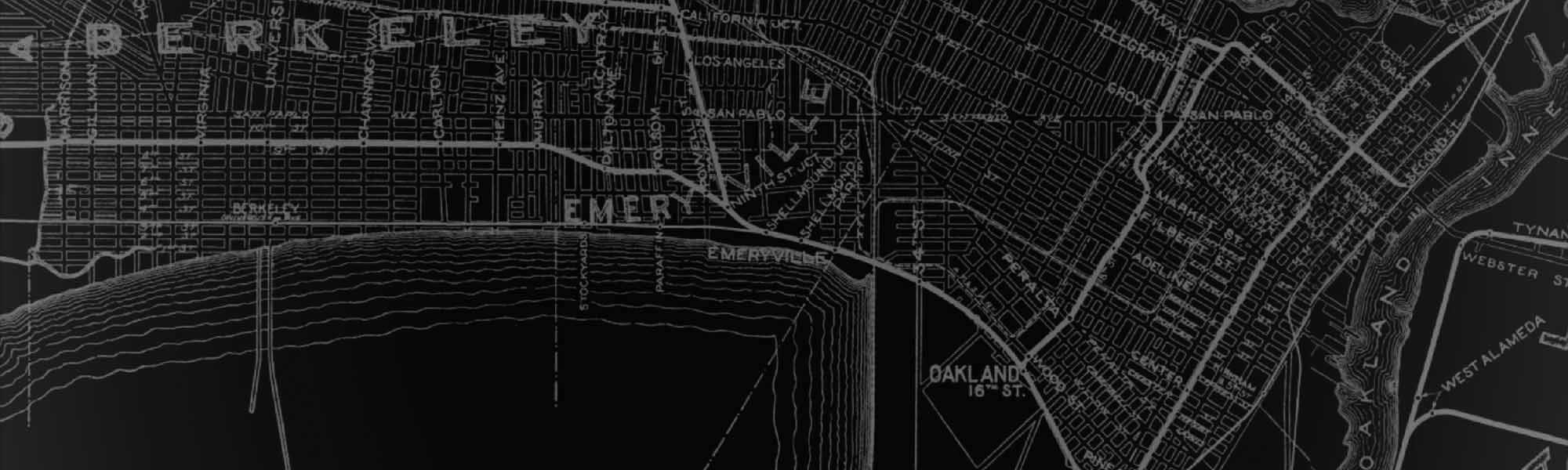

When Emeryville incorporated in 1896, the town had no city hall. For seven years, city business was conducted in two small rooms of the Commercial Union Hotel, located at the foot of Park Avenue near the Southern Pacific railroad tracks. The city government soon outgrew this space, however, and so plans were made to construct a city hall. The city fathers decided that Park Avenue should be the civic center of Emeryville. Accordingly, a site measuring 125 x 125 feet was purchased for $1,500 at the southeast corner of Hollis Street and Park Avenue. This location appeared ideal since, by the turn of the century, Park Avenue had emerged as the population center of Emeryville. The district consisted of hotels, houses, stores and saloons; a streetcar line, which began operation in 1871, connected San Pablo Avenue with Emery railroad station. At the west end of the street stood the Judson Iron Works, the largest factory in the East Bay. North of Park Avenue stretched the California Jockey Club, a horse racetrack that attracted turfmen from all over the Bay Area.

New Quarters

The new town hall was completed in 1903 at a cost of $8,491, an imposing two-story neoclassic edifice with a copper dome topped by a cupola. Designed by Frederick Soderberg, a leading East Bay architect, the structure featured a rusticated entrance arch flanked by Tuscan columns and surmounted by a copper dome.

Inside the new town hall, a graceful wooden stairway curved up to the second floor, where the spacious Council Chamber was located, its doorway framed by two Doric columns supporting a pediment. The ceiling was coffered, and wood paneling covered the walls. The first floor contained offices, while the basement accommodated jail cells.

The completion of the new Town Hall attracted the attention of local newspapers. In June 1903 the Oakland Enquirer announced that the “Town authorities of Emeryville have changed their quarters,” and continued:

“The government of the town of Emeryville has now been officially installed in the new town hall on Park Avenue. the actual moving of the effects having taken place late last week. but the ordinance authorizing the move not having been passed until last Monday night’s meeting of the Town Trustees.”

An Industrial Corridor

Soon after the new Town Hall opened, Park Avenue began to change. From 1907 to 1940, it evolved from a mixed residential and commercial strip into an industrial corridor. Several factories were built along it during this period, including the Del Monte cannery, the American Rubber Manufacturing Co., Westinghouse Pacific Coast Brake Co., Peck and Hill Furniture Co., Peoples Baking Co., and Fisher Body Service Corp., transforming the character of the street. By 1940, most of the homes and hotels along Park Avenue had disappeared, and City Hall stood in a depopulated neighborhood surrounded by factories.

Plans were made to build a new City Hall on San Pablo Avenue in the 1940s, and the old Emery mansion at 4325 San Pablo was razed in 1946 to provide a site.6 For unknown reasons the City shelved this proposal and built a fire house on the property instead. The old Town Hall survived for another 25 years at the Park Avenue location.

The Hottest session in History

On February 16, 1954, the Tecumseh Products Plant, located next door to City Hall, burst into flame. The one-story building burned with such intensity that the roof collapsed, and the brick walls crumpled. Black smoke from the fire swept through City Hall, forcing City councilmen to flee from the building. One newspaper called this “the hottest session in history.” The intense heat cracked several City Hall windows, but the building was not seriously damaged.

The completion of Watergate apartments and the Marina revived the proposal to relocate City Hall; by this time the building had become inadequate for the expanding city staff. The old City Hall on Park Avenue closed in December 1971, having served the City of Emeryville for almost 70 years. At the closing ceremony Mayor Donald Neary promised “to do everything in his power to see that the building isn’t destroyed.” The same month the new Emeryville City Hall opened at 2449 Powell Street in the Watergate complex.

Restoration

In 1973. the City of Emeryville leased the vacant Town Hall building to Bennett Christopherson. who agreed to restore the building and preserve it as an historical landmark. When Christopherson moved in, according to his account, the “building was in deplorable condition.” Over a period of years Christopherson and two other lease holders restored the building at their own expense. In 1978, the City of Emeryville, having outgrown the new City Hall and in need of extra space, went to court in an effort to break the l0-year lease and repossess the building.

The city eventually prevailed, but problems with the building eventually led to its closing. The venerable structure suffered minor damage as a result of the Lorna Prieta earthquake of 1989, which made apparent the need to retrofit the building.

The old Town Hall has been heavily modified over the years. A study of old photographs reveals that the cupola on top of the dome and the balustrade around the roof have been removed. When and why these alterations occurred is unclear. Despite these changes. old Town Hall remains an historical landmark and an architectural treasure.

This story originally published in 1996 for the Emeryville Centennial Celebration and compiled into the ‘Early Emeryville Remembered’ historical essays book.