Industry in the Twenties

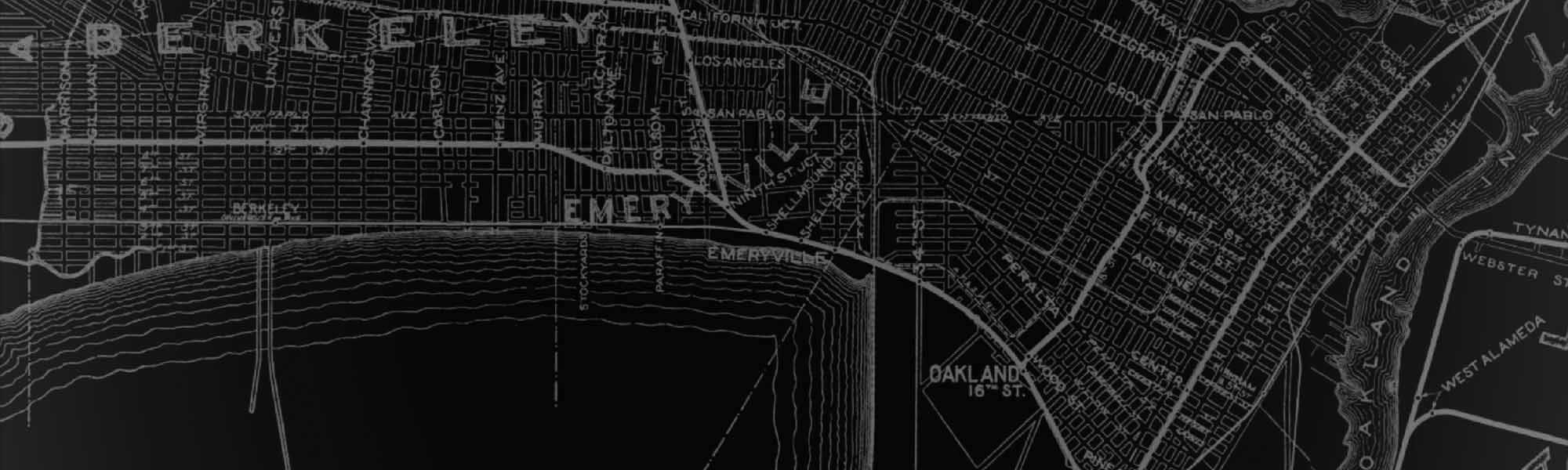

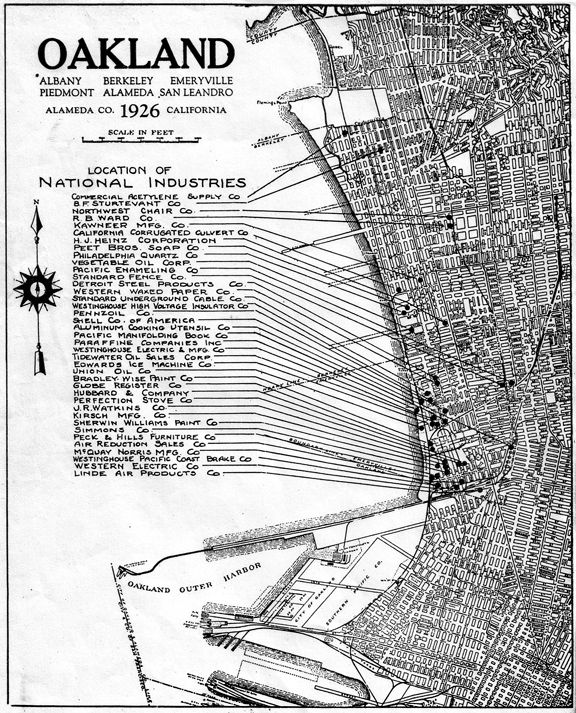

Emeryville entered a period of industrial expansion during the 20s. The town attracted industry because of its central location, low tax rate. ample labor force, and its proximity to maritime and railroad transportation.

In particular, Emeryville’s extensive transportation system provided a marketing advantage. according to the 1928 Oakland Tribune Yearbook:

“The industrial area is served by a network of spur tracks connecting with the main lines of the Southern Pacific Company and the Santa Fe Railway, both of which cross the city. The Key System Transit Company and the Southern Pacific Company operate electric passenger trains and ferries, giving rapid and convenient service to San Francisco. The Sacramento Short Line also operates trains through Emeryville to San Francisco and serves all of the rich territory to the Sacramento Valley. The street railways of the Key System connect Emeryville with all of the Eastbay cities of Alameda and Contra Costa Counties. Ocean and coastwise shipping is within a distance of two or three miles.”

Little Giant of Industry

There were other reasons why Emeryville emerged as a little giant of industry in the twenties. The introduction of automobile plants into the Emeryville manufacturing matrix contributed to its industrialization. Two large tracts of land. formerly the California Jockey Club racetrack and Shell Mound Park, became available for industrial development at this time. Lastly. the Emeryv1lle Industries Association, promoted manufacturing and worked with the city government in an effort to create a favorable business climate. By the middle of the decade, Emeryville had become heavily industrialized. The 1925 Oakland Tribune Yearbook stated: “Practically the entire city is a manufacturing District.”

Development of the Race Track

The old California Jockey Club racetrack closed in 1911 and burned down in 1915. In 1920. its owner, John Hubert Mee, converted the property into an industrial park. A 12-inch sewer pipe and 6-inch water main were installed; concrete streets and spur tracks were built so that factory sites would be accessible to transportation. These improvements cost $500.000. By 1920 a large part of the tract had been developed and sold for industrial purposes.

As a result of the industrial development of the racetrack property, Hollis Street was extended northward until it connected with Green Street, and soon evolved into an industrial corridor which continued all the way to Berkeley.

PG&E built a large 15-acre facility on the west side of the street in 1924, consisting of its main warehouse. electrical equipment repair shops, carpentry shop and a pipe yard. PG&E also built a research and testing laboratory located at 45th and Hollis Streets.

Development of Shell Mound Park

A second major tract of land. also owned by the Mee Estate. became available for industrial development in the twenties. Shell Mound Park. having been in operation for almost 50 years, closed in 1924. All the park’s structures, including the dance pavilion, band stand. shooting gallery, merry-go-round, bowling alley, grandstand, and the concession stands were removed.

The ancient Indian shellmound, on top of which a dance pavilion had stood, was leveled by steam shovels so that the property would be suitable for a factory site. Fortunately, an anthropologist was present to record data, partially excavate and retrieve some of the bones and artifacts during the leveling process.

In 1928, C. K. Williams Co., manufacturers of dry pigments, built a factory which encroached on the old shell mound site. However, the plan to develop Shell Mound Park did not materialize for some time, and most of the property remained vacant for years.

Industrial growth

Despite the failure of the Shell Mound Park development. Emeryville experienced tremendous industrial growth in the twenties. The following companies opened in south Emeryville during this period: Service Lines Inc., Fisher Body Co., Doble Steam Motors Inc., Morehouse Mustard Co., Kirsch Manufacturing Co., Magnavox Co., Pacific Gas & Electric Co., Aluminum Cooking Utensil Co. J. R. Watkins Co. and Star Automobile Agency. Several factories were also built in north Emeryville, including Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co., Detroit Steel Products Co., Western Waxed Paper Co., Standard Underground Cable, Union Oil Co., C. K. Williams Co., Frigidaire Co., New Metal Products, Associated Oil Co., Shell Development Corp., Western Electric Co., Old Trusty Dog Food Co. Drayage Service Corp., American Hoist and Derrick Co., American Tractor Equipment. and Neon Appliance Ltd. By 1930, Mayor Christie had realized his dream of transforming Emeryville into a major industrial center.

This story originally published in 1996 for the Emeryville Centennial Celebration and compiled into the ‘Early Emeryville Remembered’ historical essays book.