The Doble Steam Car

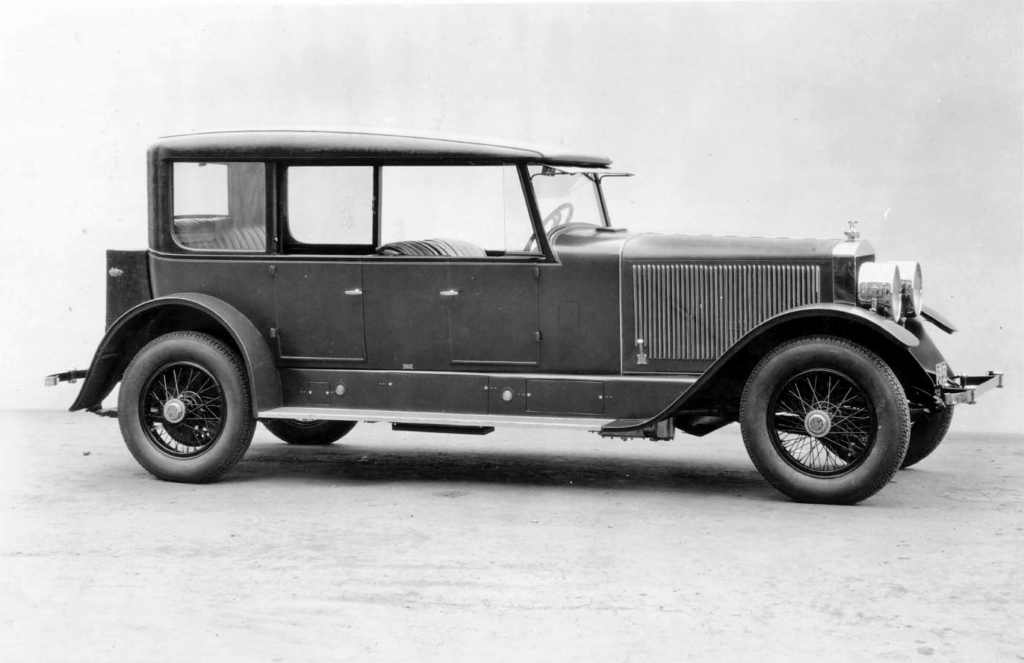

“The cars were nobly unique in every detail. They were built with as much handwork, as much attention to detail, as a fine racing machine. There was a mysterious majesty about them which derived from their combination of massiveness and the ability to go like the wind with scarcely a trace of sound.” – Griffith Borgeson

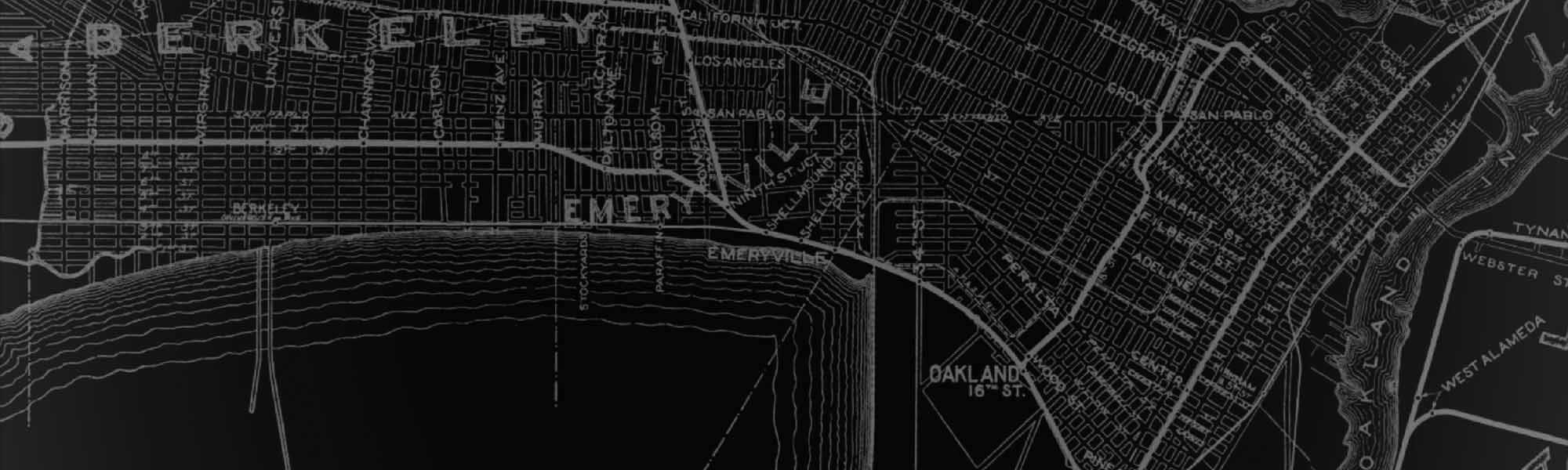

Emeryville is fortunate that many treasures of industrial architecture have survived to be recycled for new uses. One of the most interesting of these is the reinforced concrete building at 4053 Harlan Street, presently occupied by live-work studios. Originally, it was built as the manufacturing site for an automobile recognized as one of the finest of its period and certainly the most powerful and sophisticated steam powered car ever.

The Precocious Doble

The man responsible for both the building and the car was Abner Doble. Born in San Francisco in 1891, Abner grew up with three brothers in a talented family centered around the engineering firm founded by his namesake grandfather. The family firm produced tools for the gold rush. Precocious, Abner came of age intellectually in a world still dominated by the motive power of the 19th century: steam.

In 1910, Abner went to MIT to study engineering, having already produced his first steam car, albeit an unsuccessful one, while a student at Lick High School in San Francisco. Steam power was, from this early age, the central theme of Abner’s life. When he died in 1961, he was working on yet another attempt to revive the steam-powered automobile.

While a student at MIT, Abner visited the Newton, Massachusetts factory of the Stanley Brothers, then manufacturers of the best-selling steam cars in the world, the Stanley Steamer. He came away from his visit unimpressed with the Stanley’s approach to the many technical problems of harnessing steam for transport. These included long delays in start-up and the problem of partial-loss water systems which frequently led to overheating and breakdown.

Success with the Model “A”

On December 1, 1910, during his first year at MIT, Abner established a machine shop at Waltham, Massachusetts. where in 1912 he developed his first successful steam car. The Model “A” incorporated a multi-tube boiler for fast starts and a condenser capable of capturing the steam for re-use, enabling the Doble to drive long distances without replenishing water.

Five “A’s” were produced before Abner left MIT, and, with his younger brother John, he established the Abner Doble Motor Vehicle Company in Waltham to produce the Model “B.” However, under-financing caused a failure, with no Model “B’s” produced. The second major theme of Abner’s career had emerged: insecure financial underpinnings. From Waltham and the collapse of the “B,” Abner moved to Detroit and employment as an engineer with a string of automobile manufacturers. Soon, he launched a new steam vehicle project with the General Engineering Company of Detroit, using his Model “B” as a starting point for further refinement.

A Smash Hit

The Model “C” introduced uni-flow design (steam flowed in one direction only with lower heat loss), highly efficient fuel atomization and electric ignition, making the Model “C” as easy to drive as a “normal” car. At the 1916 New York Auto Show the car was a smash hit, and reportedly resulted in 50,000 inquiries and 11,000 firm orders. Before large-scale manufacture of the Model “C” could begin, however, wartime material shortages made the project unworkable.

There was a second abortive attempt to produce the Model “C” as the Doble-Detroit, but by 1919 Abner and John had sold out and moved back to San Francisco, where Doble Steam Motors was established in 1920.The new firm was initially located in a relatively small building at 714 Harrison Street, with the company contracting out much of the sub-assembly work. A wide range of steam powered vehicles was planned, from medium priced and luxury cars to boats and even an aircraft, but the designs still needed much refinement. The uni-flow design, for example, turned out to be less suitable as a flexible power source than expected, and the boiler needed to be more reliable.

Capitalizing on innovations observed in the latest San Francisco shipyard boilers, Abner adapted an existing mono-tube boiler design and abandoning uni-flow, combined it with his own two-cylinder compound engine. Incorporating the latest type of condenser and a modem chassis, the Model “D” was the best Doble yet by far, $100,000 having been invested in its development.

A modern factory was planned at Atascadero. The factory was to be of fireproof reinforced construction, with windows over 9/10 of the wall area for good lighting, as well as a steel trussed roof to allow for future vertical expansion. The building, of course, went up in Emeryville on Harlan Street instead, but not before the master plan for the company was revised.

The Magnificent Model “E”

Bypassing the Model “D,” Abner committed to a design which would be the equal of any exotic luxury car built to that time. The Model “E” was to be a masterpiece, and it had remarkable technical specifications. The number of steam cylinders doubled to four. A flash mono-tube boiler produced virtually instant start-up. All vendor components were the absolute best, from the Rudge Whitworth wire wheels and Ferodo brake linings to the Bosch electrics and the large efficient condenser, which allowed 1500 miles of driving on a 24- gallon tank of water.

The superior nature of the car’s chassis was crucial to successfully raising the capital necessary for the project. The Doble brothers were on their own this time, and backers would be suspicious of a steam-powered car if there was any hint of weakness. Before capital could be raised, the state commissioner of corporations, Edwin Daugherty, required examination of the company by an outside expert. In October of 1922 that examiner, R. A. Wilson, reported concerns about the Doble’s plans for production, but expressed unreserved approval of the car, describing in appreciative detail the sturdy efficient boiler and the sophisticated controls. Doble Steam Motors Corporation was soon registered in Delaware and 500,000 shares of stock offered at ten dollars per share.

A New Factory in Emeryville

On May 26, 1923, ground was broken for the new Emeryville factory and headquarters of Doble Steam Motors. When production of the Model “E” commenced less than a year later, the car was indeed remarkable. First of all, the car was fast. The acceleration rate of the Doble Model “E” was more than twice that of any other car made in 1924. The car was also remarkably easy to drive, as owners enjoyed demonstrating. Marin Avenue in Berkeley, with a challenging 1 in 4 gradient, was often used as a test drive, probably for the incredible effect on a novice as the car was brought to a halt, held on the throttle without brakes, and then driven noiselessly up the hill at gathering speed. Abner’s over-engineering produced a car with 1,000 pounds of torque available sitting still. With 1,500 PSI of working pressure, the car’s enormous reserves of power helped make it extremely reliable. (In service, Dobles would routinely accumulate mileages of more than 200,000, and a Doble E-13 accumulated more than 600,000 miles).

High Prestige Among the Wealthy

Along with its highly capable chassis, the new Doble had the finest coachwork. The bodies were made by Murphy Company of Pasadena, noted for spare, exquisite open cars and close-coupled sedans with sporting lines. All Murphy bodies were made with beautiful craftsmanship and extraordinary attention to detail. Murphy-bodied cars already enjoyed high prestige among wealthy southern Californians, and the Doble’s combination of world-beating performance, luxury and high style quickly attracted the patronage of Hollywood stars and the wealthiest of the social elite. Howard Hughes, Norma Talmadge and Joseph Schenk all bought Dobies, and a healthy international market for the cars quickly developed.

The potential problem of transporting bare chassis from Emeryville to Pasadena was solved by simply driving the naked chassis the 600 miles using a crude temporary seat platform and instrument panel. This practice became a very effective way of testing each car and correcting any problems before the cars were clothed with their expensive (and vulnerable) aluminum body work.

At Pasadena, each chassis received body, trim and upholstery individually selected by the client. When the cars left Emeryville, each chassis had a wheel base of 11 feet, 10 inches, weighed about 3,000 pounds and cost about six thousand 1925 dollars. By the time Murphy finished their work. the car weighed from 4,000 to 4,500 pounds and cost between nine and eleven thousand dollars.

A Retrograde Project

Trade was brisk for such an expensive automobile, but production was astonishingly slow, mainly due to the extremely close tolerances required to contain 1,500 PSI of steam pressure. Mass production simply wasn’t feasible for the elaborate Model E, so in 1923 Doble launched a surprisingly retrograde new project, the Doble-Simplex. Using the chassis of a Jordan Big Six, the Simplex prototype inexplicably returned to the discredited uniflow engine and used many features of internal combustion-type cars in an effort to cut costs.

Production of the Doble-Simplex was planned for 1924, at a price of $2,000. This was low for a Doble, but a lot of well-built cars with established reputations were available for that kind of money. When the problems of low efficiency and rough running (experienced with the Model “C”) resurfaced in the Doble-Simplex, the project was abandoned with only one car having been built. With the demise of the Doble-Simplex, prospects for mass manufacture of Dobles in Emeryville vaporized, and the plant was relegated to manufacture of very limited quantities of very expensive cars.

In April of 1924, in the first report to stockholders, Abner reported that the Emeryville factory was up and running, with an annual capacity of 300 cars, and that the building, machinery and inventory were paid off. Projections were made for an expansion vertically as car sales grew, to an eventual capability of 1,000 cars per year. Unknown to Abner at the time of the report, however, the stock offering by Doble Steam Motors Corporation had turned into a disaster.

Bombarded by Lawsuits

In the free-wheeling stock market of the 1920s, many of the controls on trading stock that we currently enjoy were not in place. Thus, Doble stock, both real and fraudulent, was used in several major stock swindles. By the time Abner belatedly learned of the fraud, the company was in serious danger. Abner quickly attempted to cover the fraudulent shares, but the commission on corporations refused to allow more shares to be issued and the company was bombarded by lawsuits. The court proceedings went just about as badly as possible. At their conclusion, the company was required to pay 30 cents on the dollar for stock it had never issued or profited from, and Abner was held personally liable for the payments and even briefly sentenced to jail. The perpetrator of the fraud pled guilty and was fined a mere $5,000.

Finished off by the Crash

In the aftermath of the stock fraud and legal proceedings, employees at the Emeryville plant had to be laid off, machinery sold and plans for plant expansion abandoned. Capital for Doble Steam Motors was now impossible to raise. In spite of these cataclysmic setbacks, the Doble brothers were true believers in steam power and stayed at it. They bought shares of their company on the open market to repay legitimate subscribers. Research and development continued, although very few cars were produced. In the late 20s, the “F” model was developed, with a new firebox, higher steam pressure and more efficiency. Some older Dobles were modified or updated. Finally, though, in spite of the tenacity and commitment of the Doble brothers, the stock market crash of 1929 finished off the company, sending Doble Steam Motors into liquidation in April of 1931. Later in the year, the Emeryville factory was bought by George and Wilham Besler, sons of the chairman of the Central Railroad Company.

Taking Steam Power to New Heights

Apparently, like many players in the Doble story, Bill and George Besler had a bad case of “steam disease”– a fascination with the instant, silent power of steam. Both brothers had been employees of Doble Steam Motors before the crash, and when the company was liquidated, the Beslers were able to raise enough capital to keep the factory intact. The Beslers also acquired the rights to many of the Doble patents, and with their fresh capital were able to develop several successful industrial products. In one sense, the Beslers succeeded in taking steam power to new heights. In 1933 they realized Abner’s 1920 dream of applying steam to every mode of transport when they built and flew a steam-powered aircraft.

The end of the Emeryville venture by no means marked the end of the Doble brothers’ interest in steam transport. When the company was finally out of their hands, Abner and Warren, exhausted from the personal cost of the liquidation, began traveling. The universal recognition of Doble engineering prowess brought job offers from around the world.

Consultants on Steam

Warren became a consultant to two German manufacturers of commercial vehicles: A Borsig Co. of Berlin, and Heuschel and Son of Kassel. Abner went first to New Zealand to supervise the steam conversion of an A.E.C. bus by the A & G Price Co. of Auckland. Although technically successful, the end product’s cost could not compete with the ubiquitous diesel. Abner then joined the Sentinel Steam Wagon Co. of Shrewsbury, England as a consulting engineer.

In addition to his consultancies abroad, Abner wrote frequent articles on the technical aspects of light steam power and, after returning to the U.S. in 1937 and sporadically throughout the war years, he served as consulting engineer on many projects.

A Steam Car Revival

In 1940, Abner became involved in a steam car revival project launched by his good friend Charles Keen of Madison, Wisconsin. Like Abner, Charles came from a “steam family,” his father and uncle having built a small steam-powered “horseless carriage” in the 1870’s.

The project was based on a Stanley Model 60 engine and rear axle, with a steam generator specially constructed along Doble principles. The Keen-Doble power plant utilized a flash boiler and electrically ignited atomizing burners, and the controls, pumps and exhaust turbine all followed the usual Doble design. Most of the effort went into the drive train, and the rest of the car seemed almost like an afterthought. A modified Willys chassis was employed, complete with its braking system designed for a much smaller and lighter car. The body work was a riot of mismatched panels, with the hood and front fenders from a ‘42 Plymouth, the cowl, dash and doors from a ‘39 Chevy, and the rear sheet metal from a ‘40 Plymouth.

A Keen Steamliner prototype was on the road by 1940, but in classic Doble fashion development continued. In 1957, Mechanix Illustrated reported that over $100,000 had been spent on the project. The car saw daily use by several owners before the superheater burned out in 1968. The car survives in derelict condition.

Ambitious Plans

In 1946, Alex Moulton, the designer of the suspension for the Austin mini, began a steam car project called Steampower Ltd. Twelve years before the transverse front-wheel drive mini, Moulton proposed such a layout employing a two-cylinder steam engine from New Zealand, based on work Abner did there in the thirties. Steampower Ltd. went quiescent in 1951 when Moulton Developments Ltd. was formed, the chief draftsman moving to California to join Doble on a new project.

The McCulloch Corporation of Los Angeles, headed by Robert Paxton McCulloch, had ambitious plans for a modern car based entirely on Doble designs. Abner’s personal car, E-24, located in England, was purchased by McCulloch to serve as a model. A very attractive prototype was produced, with a body designed by Brooks Stevens. But the car apparently never ran. Once again. the elaborate controls necessary for automatic operation consumed so much development time that a practical consumer product was never attained. In 1954, citing the vagaries of the tax code and the difficulty of competing with the extensive development of the internal combustion engine, McCulloch Corporation closed down the project.

Million-Dollar Contract

Meanwhile, the Beslers prospered. They produced the last of the Doble cars and explored alternative applications for the Doble power plant. The most spectacular of the latter was achieving the only flight ever made of a steam-powered aircraft (the power plant is on view at the Smithsonian). Others included modular boilers for industry and the Bee-Spray and Bes-Kil agricultural sprayers. During World War II, the Beslers developed and manufactured fog generators for the military, earning the Army-Navy “E” for excellence.

George Besler became president of Davenport Locomotive Works, license holders of Doble patents. Bill Besler continued working with Doble cars and obtained a million-dollar contract from G.M. to develop a steam powered ‘69 Chevelle Malibu during a period of congressional interest in low emission alternatives to the gas engine.

Dreams Nearly Realized

Abner Doble passed away in 1961, taken by a heart attack in Santa Rosa at the age of 70. He was robust and active in steam projects right to the end. The factory built as the headquarters of Doble Steam Motors still stands at the edge of old industrial Emeryville–a reminder of how the Doble brothers’ steam dreams were nearly realized.

This story originally published in 1996 for the Emeryville Centennial Celebration and compiled into the ‘Early Emeryville Remembered’ historical essays book.

Karl A. Petersen

Sorry your essay has not received more recognition. I was curious that two photos were not credited, but one was: (Photo: Doble Steam Motors Co. Photograph Collection). Where is this collection? I am researching and writing on the Doble history and projects.

Emeryville Historical Society

These photos are available on The UC Berkeley Digital Collection (search ‘Doble Steam Motors’ or ‘Abner Doble Papers’):

https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/find/digital-collections

Emeryville Historical Society

Hi Karl

I don’t know if everything Jim Crank had in his archives went to UC Digital , but I understood that he had rescued the Doble Business Archives , presumably from the Beslers , and held them at his Redwood City workshop .

Jim’s passed away since I knew him , and Barney Becker was the only other person I can think of who might have ended up with anything Jim didn’t have , but I think Barney’s gone too .

The only photos I supplied were taken at Pebble Beach . Don Hausler helped me access the Oakland Library’s collection ….. I’m sure he could fill in the gaps .

Best regards, Phil

Karl A. Petersen

To:

Phil Stahlman

philstah@gmail.com

I do have the images from UCB digital archive and images of the rest of the Doble collection other than the largest items (which were bought up for me the day the library closed because of a security system failure and I didn’t have the $4000 to make another trip). I also have images of Jim’s collection including all the items he pocketed from the Bancroft.

Some items of Warren Doble are also in the collection.

Jim did not have the Besler business files. They were donated separately and the library consigned them to a dumpster. By some quirk of fate, a dumpster diver obtained a portion of these files and they are in the collection of Tom Kimmel.

I was unaware that the Oakland Library has such a collection, and will be delighted to contact Don Hausler.

I have tried to contact the Oakland Chamber of Commerce. They put a great deal of effort into the 1923 parade and show in honor of the Doble Steam Motors groundbreaking in Emeryville and may well have an interesting file somewhere.

I continue to research and write the historical Doble story.

Aaron

Hi,

Would you be so kind as to share the files? Do you have the part and assembly drawings for the cars? It would be incredible to be able to make a reproduction car.

Sincerely,

Aaron

Aaron

Hi Sir,

Do you have the part and assembly drawings with dimensions? If so, would you be so kind to share them? It would be really neat to be able to build a reproduction car!

Sincerely,

Aaron