Shell Development Research Center

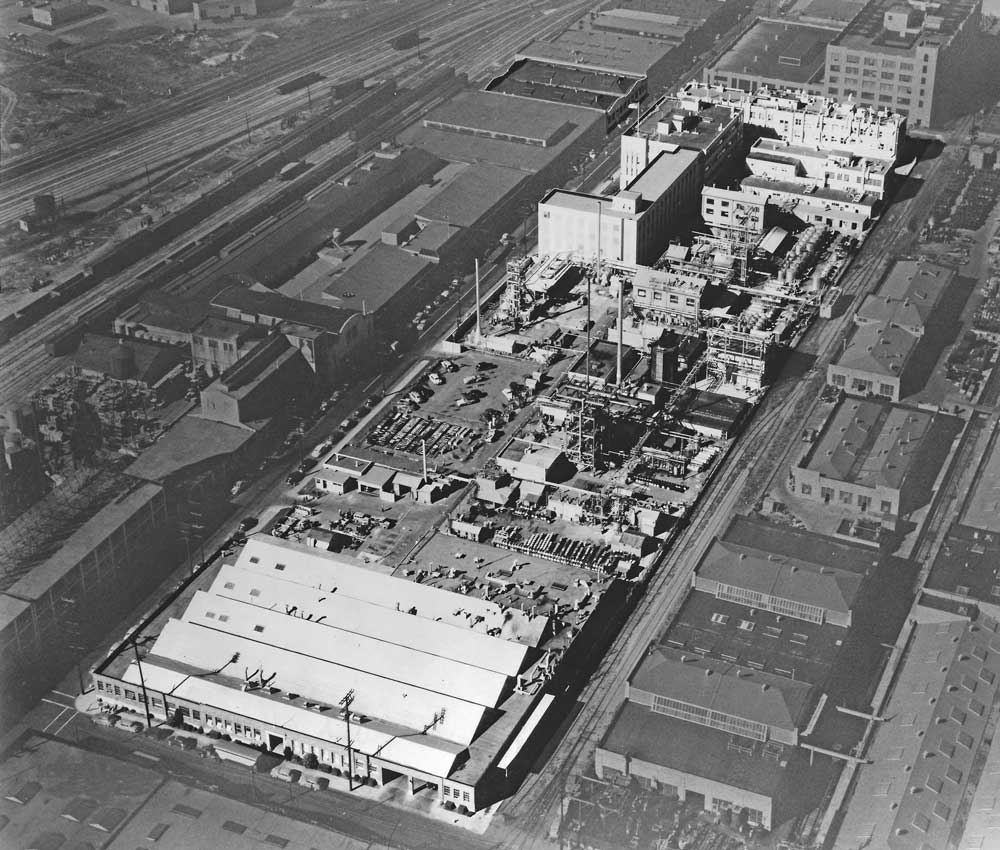

This laboratory on Horton & 53rd streets, currently operated by Spanish pharmaceutical giant Grifols, has been an influential site for scientific research for nearly a century. At its peak, the campus anchored by this building spanned 24 acres, included 90 buildings and employed 1500 workers.

Shell Oil, founded in 1907 through a merger between Royal Dutch Petroleum and The Shell Transport & Trading Company, was the largest producer of oil in the world by 1920.

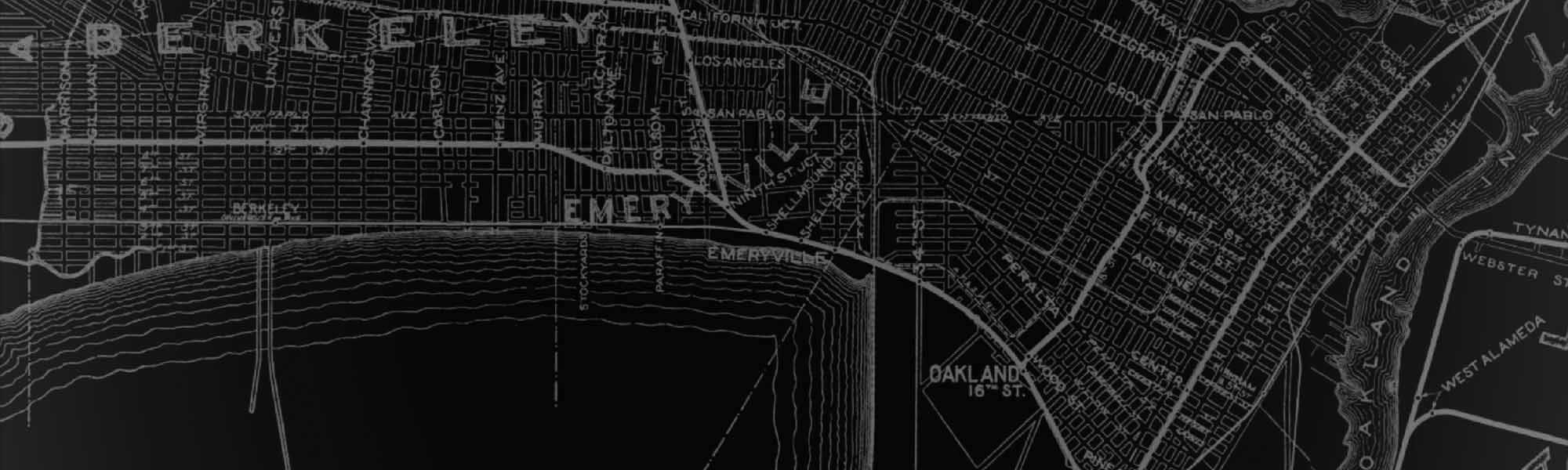

In 1928, Shell entered the chemicals industry and settled on this site previously occupied by the California Jockey Club horse racing track.

The site was near the Southern Pacific Red Line tracks that connected Emeryville to the University of California campus and Downtown Berkeley.

It was also within close proximity to Shell’s refinery operations in Martinez and their chemical manufacturing plant in Pittsburg, CA.

The first research facility constructed was 30,000 sq. ft. and employed less than 40 workers. At the time it was considered among the “largest and most modern research laboratories in the United States.”

The purpose of the plant was to explore what products could be produced from crude oil and was labeled “The University of Petroleum.”

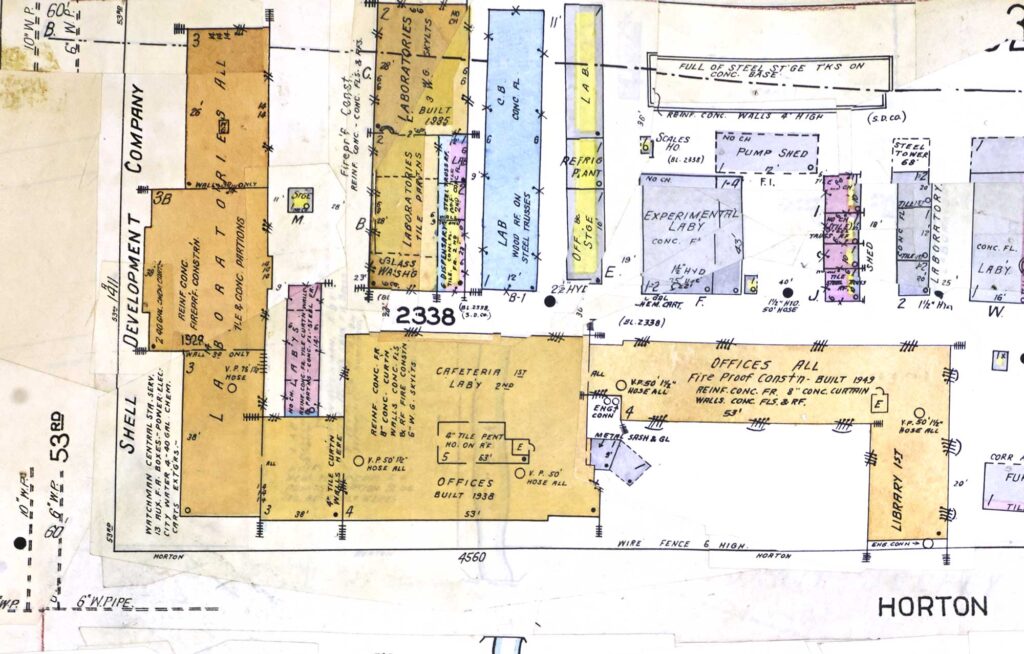

In 1937, this Shell facility continued to rapidly expand, constructing a new $500,000, 4-story research and laboratory building, doubling the capacity of the original plant.

The new addition was four stories high and connected to the original plant on the western side. The new building contained laboratories, pilot plants, a library, study rooms, service departments, administrative offices and an employee dining room.

In 1939, Shell purchased an adjacent parcel in order to expand their research and development operation. Close to $1.5 million was invested in a new laboratory that employed an additional 500 people.

The massive facility made significant contributions to allied efforts during World War II including formulating a special, high performing aviation fuel. Also during this period, the company began hiring female chemists who contributed their expertise to develop products to help advance the country’s war efforts.

The research center also had ties to famed physicist Robert Oppenheimer who was said to have been an offstage force in unionizing parts of the facility’s workforce. Oppenheimer is also said to have actively recruited Shell employees for the Manhattan Project that he of course directed.

A five-year expansion project was completed in 1960 that doubled the campus’ available space. A five-story warehouse was acquired in order to increase the size of the operation.

By 1965, the facility had a workforce of more than 1,400 employees and encompassed 90 buildings accounting for over 500,000 square feet of space.

Throughout its history, the facility spawned the invention of several fuel additives, epoxy resins and a synthesized rubber.

They also made many contributions to the U.S. space program, including development of rocket fuels, and handling techniques and storage methods for these highly explosive compounds. Shell Development’s labs also contributed significant support to California-based land speed record holder Craig Breedlove and the Spirit of America vehicles.

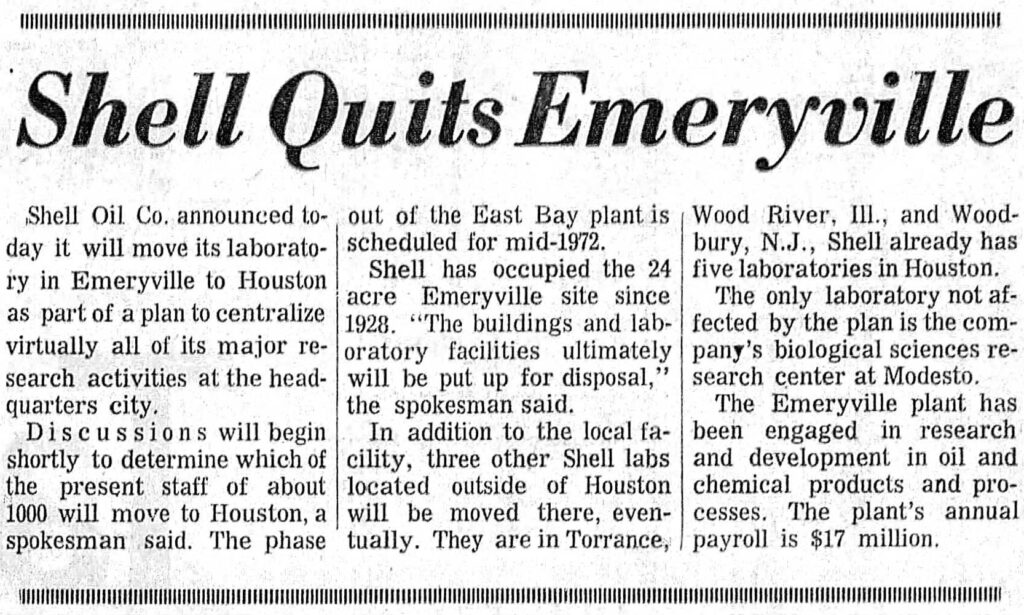

Shell Development relocated to Houston in 1972 to centralize their operations. More than 1000 employees were relocated.

Many components of the lab were demolished but some of the office space was repurposed for other uses. Some of the properties later became an early home of biotechnology pioneers Cetus and then Chiron who continued to expand their campus.

For over forty years following Shell’s departure from Emeryville, former employees continued to meet in Emeryville to socialize. Surviving members eventually dwindled and these meetings ceased in 2007.

Chiron was acquired by pharmaceutical giant Novartis in 2006. Grifols acquired Novartis’ diagnostics business in 2013 and still currently resides there.

Among the artifacts from Shell’s tenure are several logo medallions on the facade.

The southern end of the campus along 45th street became the Emeryville Artist Cooperative.

A more comprehensive account of Oppenheimer’s involvement with the Shell Research center can be read on The E’ville Eye.